I value the tessitrici artigianali, the women handweavers of Sardinia, as artists worthy of respect in their own right — not as producers of other peoples’ designs.

Over the years, I’ve come to realize that not everyone regards the handweavers in this way. I’ve been contacted by many interior designers and clothing designers that view the Sardinian handweavers merely as potential producers of the designers’ own items. I’ve also been contacted by large companies that see the tessitrici artigianali only as possible sources of Sardinian textiles that can be copied and produced in the corporation’s offshore factories.

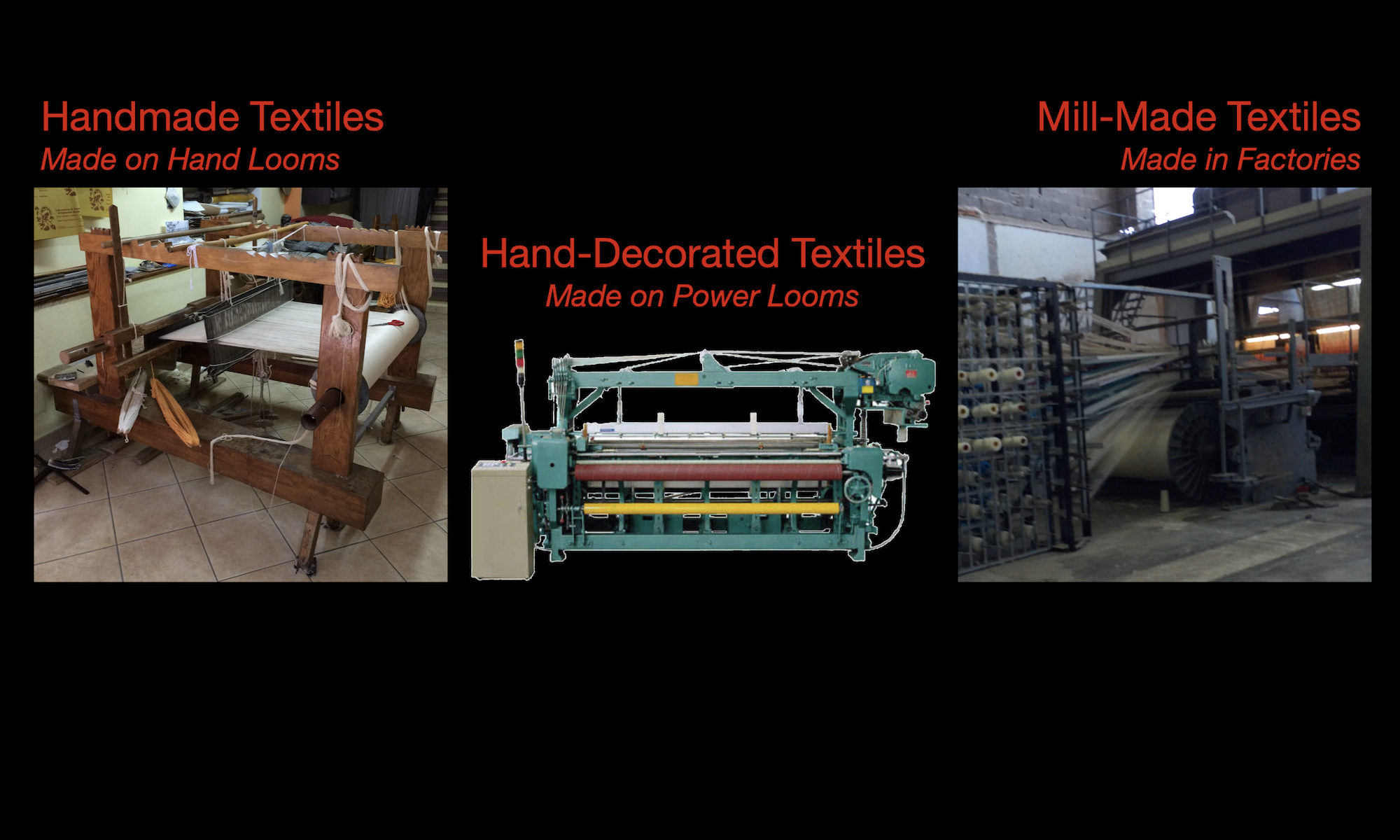

Most interior designers seek textile producers to make rugs or other articles fashioned by the interior designer. The designers want the articles produced exactly to their specifications at a low price — a price which is at least doubled, sometimes tripled or quadrupled, for the designer’s profit when selling to their client. The interior designers command an even higher price from their client by stating items are “Handmade in Italy” — even when the articles are not truly handmade, but are made in power-loom shops — and even when the additional profit gained from the “Handmade in Italy” label is not shared equitably with the actual makers, the weavers.*

Clothing designers also seek textiles “Made in Italy” for the increased status and payment the “made in” and “handwoven” labels will bring, yet the designers generally do not want or value the finished integral textile art created by handweavers. Fashion designers merely want low-cost fabric they can use as a component in their own label of bags and clothing, not the beautiful rugs, bags, table runners, and other finished works created by the handweavers.

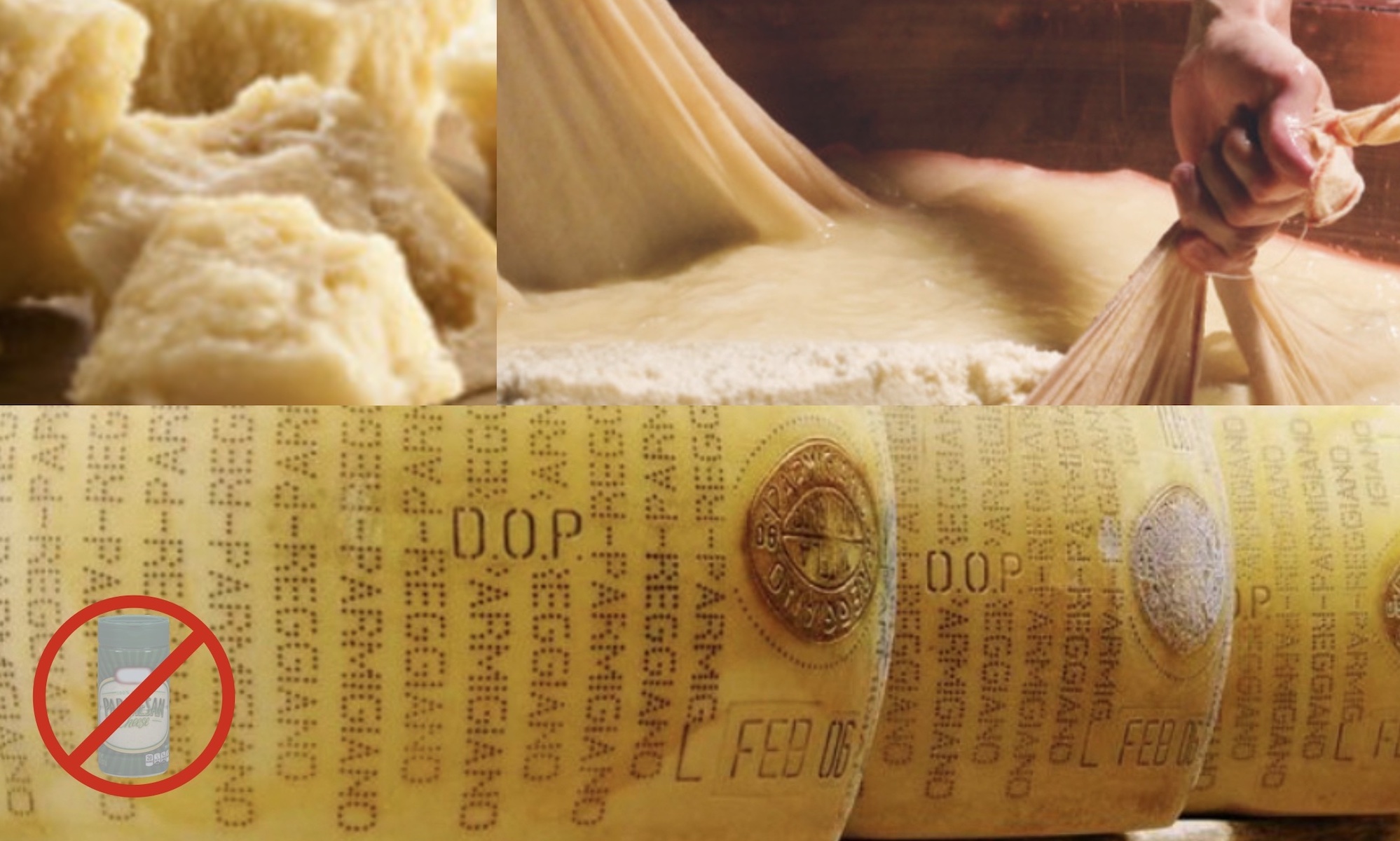

Similarly, large multi-national fashion houses often seek to “source” fabric and designs from Sardinia. When I’ve questioned the representatives who have contacted me from such corporations, they’ve brazenly confirmed they want Sardinian textiles to copy for corporate-branded items that would be made in corporate-owned mills in Asia, and sold for corporate profit. At least two of the corporate reps have hinted that I would be well paid if I were to provide them with samples they could copy — which I do not. After I refused one corporate rep, he even tried to pose as an independent individual by contacting me from his personal email address to request samples.

As well as having said “No!” to these large corporations, I’ve declined to work with designers and small business owners who have sought to appropriate Sardinian textiles and/or designs for their own profit, and without giving due credit and pay to the handweavers. I don’t support or participate in such activity — it’s not respectful or dharmic (right action).

While individuals and cultures always influence one another, outright intellectual and artistic theft, cultural appropriation, and colonialism have run rampant across the world for centuries. These activities negate cultures and individuals, and have created a social, economic, and ecologic mess across the globe. To steal the designs and heritage of the traditional women weavers of Sardinia for the profit of foreigners is not right. To consider the tessitrici artigianali merely as producers of items that will profit foreigners is also not right.

The tessitrici artigianali are endowed with an esteemed heritage, possess incredible artistic and design skill, and apply time-honored STEM (Science, Technical, Engineering, and Math) and problem-solving skills in all aspects of their work. The women weavers lovingly and skillfully create textiles of modern and ancient design — art of their own, and art of tradition. The ancient and modern handwoven textiles of Sardinia are museum-quality works of art, created by artists who are invisible to the world primarily because they are women, and also because they are from a small island discounted by the commercial world except as a source of cheap labor or goods. To purloin the art and skills of the tessitrici artigianali for off-shore profit is adharmic — not right.

I firmly believe that to change the world, we must change how we are in the world — and this includes changing how we do business. Respect for one another, for the earth, and for ourselves must be foremost, and we must keep this respect in mind when we act, including in business. This concept is not new; it’s actually rooted in ancient traditions of all lands, including India, the Americas, and Sardinia. In reality, the slowly-growing interest in ethical business is a resurgence, not a new concept. As part of this resurgence, the peoples, arts, culture, heritage, wisdom, tangible riches, and intangible wealth of all lands — including Sardinia — must be recognized and honored.

The fact that many in the United States do not know about Sardinia and its grand history is no excuse for refusing to learn about, acknowledge, or respect the island’s vast heritage. Sardinia was a key player economically, culturally, scientifically, and politically in Early and Modern European, Byzantine, Roman, Punic, Phoenician, and other time periods. As recently as 1860, The Kingdom of Sardinia extended over a large portion of Continental Europe. Prehistoric Sardinia was as magnificent as Egypt, Mesopotamia, Colombia, and other areas that were once centers of civilizations that are now lost. The architecture, arts, crafts, music, science, and other aspects of Sardinia’s cultural and heritage have been — and still are — overlooked, discounted, and even intentionally destroyed by classic historians and academics.

The Sardinians are keepers of great gifts. This is especially true of the tessitrici artigianali, who bear the wisdom, traditions, and skills of their art as well as a compassionate manner of curating their work and world. The consideration, attention, and love the women weavers bring to their art and lives is lacking in the world of technology and business. This lack is largely responsible for the sense of “something’s missing” that many people feel. Consider a meal prepared with home-grown ingredients and cooked for beloved family and friends; a shirt made by hand with attention to detail and loving throughs for the person who will wear it; or a handwoven rug carefully, thoughtfully, lovingly made by an artist: The essence of what these give us is unquantifiable and inimitable, even by the best technology. These items are made with care and love, the invisible building blocks of a diverse yet complete humanity.

Our planet and our humanity are being threatened to the point of destruction by greed, hatred, and indifference. Bringing respect, care, and loving attention into our actions and the items we use will help restore our humanity to each one of us. As individuals who live and act with care, attention, and compassion, each of us can help restore humanity to the world.

While it may seem a small thing to respect the traditions, art, and rights of a small group of strong women handweavers in Sardinia — the tessitrici artigianali — we must remember what ancient cultures have long known, and modern science is rediscovering: no one and no thing is small, or independent. We’re all interconnected and interdependent parts of a greater whole, like the individual fibers of a handwoven rug.

~ KM Koza

*I believe interior designers and power loom shops are a perfect match, but the articles made in power loom shops are not truly handmade — they are hand decorated, and calling them handmade only confuses buyers and in the end hurts all weavers and textile producers.