Small things make a big difference.

My favorite way to illustrate this stems from design school. Back in a time when we drew straight lines by hand using T-squares, triangles, and Rapidograph pens, we used a simple exercise to demonstrate that absolute care, attention, and precision was necessary in creating the very first to the very last element of a project.

Think of drawing horizontal lines on a piece of paper to emulate a 8.5″ x 10″ sheet of notebook paper, which generally has about 32 lines. If you were to draw the lines by hand, you would start from the bottom of the page, draw a base line, use that line to align and draw the line above it, and then use the newly-drawn line to align and draw the line above it, continuing this process until all lines on the page are complete.

If the very first line you drew was off level by 1/32 of an inch — the width of a fine pen nib — your design would be ruined: by the top of the page, after repeating the 1/32 inch error 32 times, your top line would be tilted one inch.

Now think of an architect guiding the construction of a skyscraper a hundred stories high, and the precision with which the foundation must be laid. Consider a handweaver making a bedspread that requires weaving thousands of crosswise weft-fibers, and the careful alignment necessary for the first row, and every row, of fibers. Think of the navigators, mathematicians, and engineers calculating courses for ships traveling oceans, skies, universes, and how the initial degree, minute, and second of direction must be absolutely precise, and then checked and corrected constantly to ensure the ship reaches the intended destination. The tiniest bit of imprecision — or an unseen factor affecting calculations or the project — would drastically change the outcome.*

Simply put, the tiniest detail affects the outcome in ways we can’t imagine.

This is true within and beyond architecture, construction, navigation, sciences, arts, and crafts. This is true in everything — and for everyone. This is true for presidents, prime ministers, actors, sports figures, scientists, saints, mystics, people of fame — and each and every one of us.

Each one of us affects the whole. And each of our actions affects the whole.

This can be staggering to consider — yet this realization is also a gift, a blessing.

If each of us, each of our actions, each of our interactions, each of our words affect the whole, affects our world, how do we watch, use, care for our actions, our words, and that which we contribute to our world?

Do we, in our personal spheres and work, act with disregard, condescension, hatred, and anger, spewing toxic dark clouds of negativity that increase with time and distance to create chaos, war, and destruction on a global scale?

Or do we bring awareness, compassion, love, and care for small things into the tiny moments of our daily lives, filling what we touch with light, harmony, and joy — all of which increase with time and distance to create a world more beautiful, inclusive, harmonious, and supportive that we can perhaps imagine?

When we realize that we’re all connected and that each one of us contributes to the creation of the world we share, I believe we have the responsibility to act upon that realization: to live with love, act with compassion, care for small things, and give attention to the tiny moments of life.

If the tiny things are cared for, if small acts are done with love and kindness, if we bring joy to our work, if we treat people, animals, plants, nature with compassion — imagine how the results would — will — magnify.

Can we each play our part, no matter how small it seems, to help the world change for good, beyond what we can imagine?

I think of those so often invisible in our modern world, and what they bring to us. Living and working with care, compassion, love, and awareness are mystics, mothers, artists, and others, including handweavers.

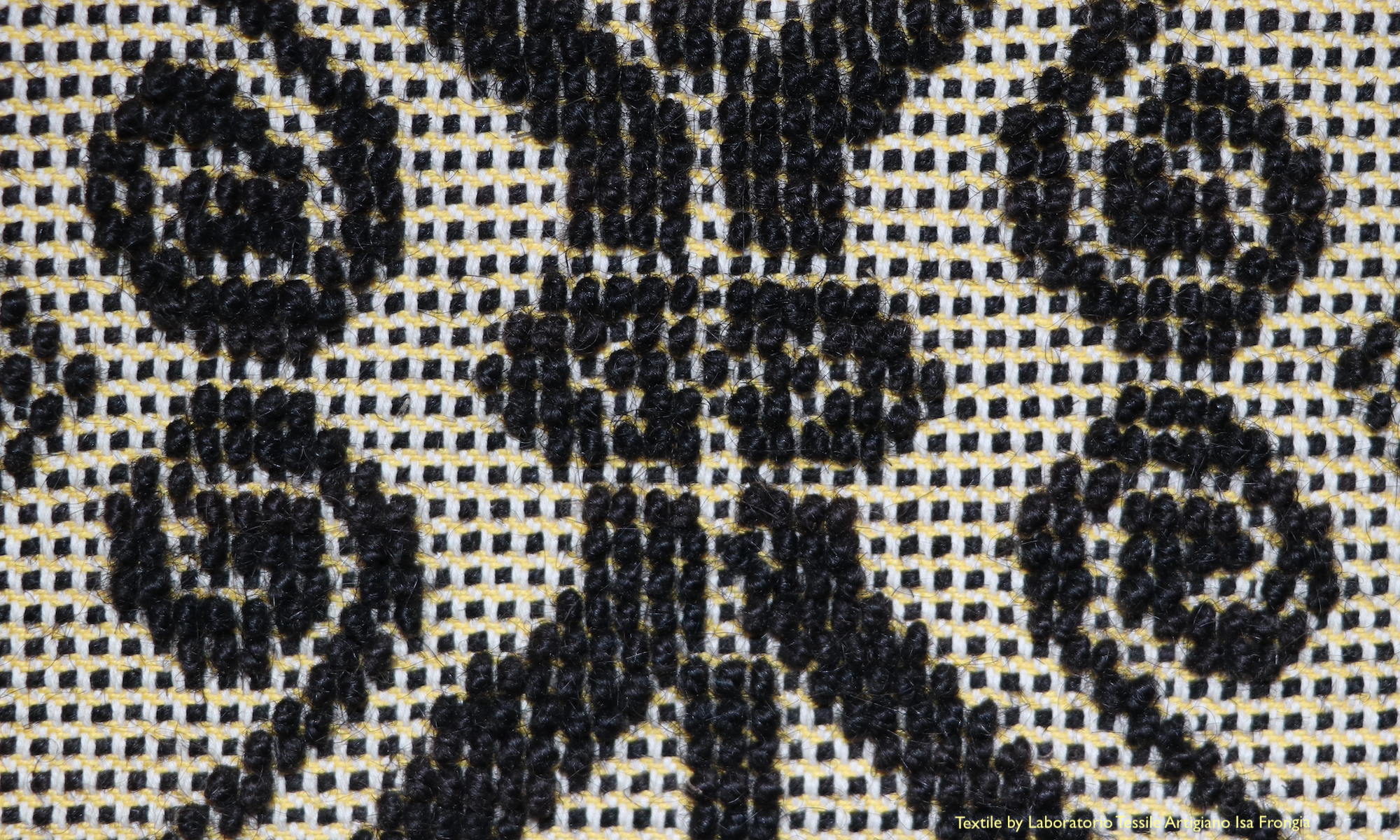

Women weaving in the hills of Sardinia; rebozo weavers and lace-makers in Oaxaca and Teotihuacan; Native Americans weaving in the Southwestern U.S.A; rug-makers weaving in the Middle East; sari-weavers in India; and others comprising the dwindling numbers of handweavers: All are working with care, focus, and attention, placing and aligning each fiber of every textile they weave.

Beautiful textiles are the visible, tangible result of the precision and care handweavers bring to their work.

But what are the invisible, intangible results?

Perhaps the fragile balance of our world is subtly maintained by the magnified effect of the order, precision, care, and love the handweavers bring to their work.

Who’s to say otherwise?

*Professor Edward Lorenz famously discussed how small acts — the change of a single variable in a set of conditions — would be magnified over time and distance and thus change outcomes. This has become known as the “butterfly effect”, simply stated as a butterfly flapping its wings in one part of the world could cause a typhoon on the other side of the world.

###

© 2020 KM Koza

This piece is also posted on Tramite.org.